Raffles and the British Invasion of Java

Raffles and the British Invasion of Java is a new narrative history book by author and travel writer, Tim Hannigan. It tells the story of the strange years between 1811 and 1816 when Britain ousted Holland from Java and gained control of the nascent Dutch East Indies.

At the head of the Interregnum was a young Thomas Stamford Raffles, best remembered today as the "founder of Singapore".The British Interregnum was a period of furious controversies, bitter in-fighting, and dramatic changes in the balance of power between Javanese and Europeans, and it helped set the tone for the coming colonial century, in Indonesia and beyond.

Raffles meanwhile, usually portrayed as a "liberal", visionary and hero, presided over all manner of thoroughly illiberal actions in Java...Over the coming months posts will appear on this blog telling various stories from the British Interregnum and the wider historic context in Java and Indonesia - the sidelights and footnotes that could not find space in the published book, but that are far too interesting to leave out altogether!

For more about the published book, see www.rafflesandjava.com.

Archives

Monthly Archives: December 2012

Horsfield’s Holocaust

The Dread Poison Tree

Dr Thomas Horsfield was perhaps the most unlikely of all the foreigners in Java during the British Interregnum. An American medical doctor from a strict Moravian upbringing in Pennsylvania, he had come to Java in 1800 and quickly discovered botany to be more rewarding than either medicine or Christianity. He had been based in Surakarta ever since, pressing flowers, climbing trees, and setting up what could probably be regarded as the first zoo in Java. The Dutch had paid him a small stipend, and Raffles followed suit.

During the British Interregnum Horsfield became a fixture of the Batavian Society, a group of colonial gentlemen who would gather in the capital to hear readings on a wide range of subjects, some not entirely suitable for serious scholarship. The most dramatic of the papers that Horsfield read to the society dealt decisively with a topic that must have cropped up in the conversations of many of the recent arrivals in Batavia. After all, who hadn’t heard of the fabled upas, the Poison Tree of Java?

Demolishing the Legend

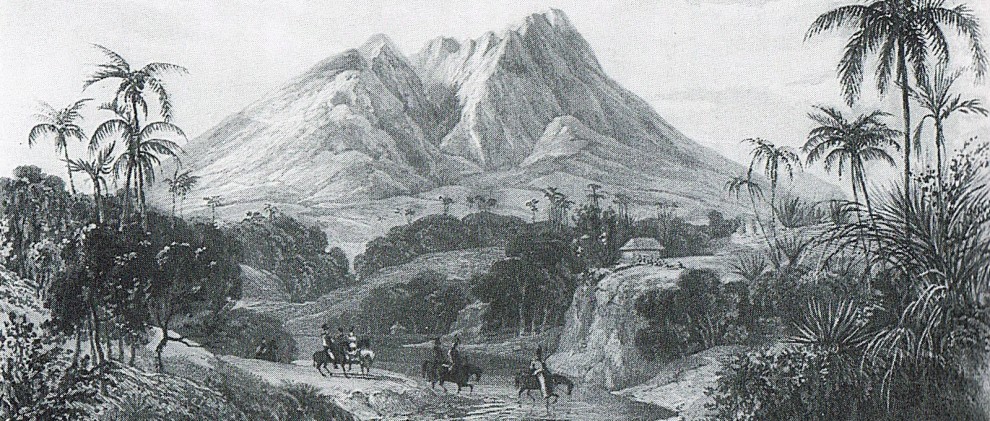

Though the fabulous account of the infamous fantasist J.N. Foersch had already been widely discredited, outside of scientific circles his tale of poisoned uplands, certain death, and dramatically dying damsels was still common currency. Like all serious scientific people, Horsfield looked on the fabricating Foersch with a mixture of contempt and rage. ‘The literary and scientific world has in few instances been more grossly and impudently imposed upon than by the account of the Pohon Oopas’ he wrote. Horsfield himself had first come across the upas (which he often called by its more common Javanese title, ancar, from which its scientific name – antiaris – was later taken) in the dense, tiger-haunted jungles of Banyuwangi, beneath the great cone of the Ijen Volcano where Java is cut short before Bali and where they possess the strongest black magic in the whole island.

Thomas Horsfield – Missionary, turned doctor, turned mad scientist

He made it very clear that the stories of a barren wasteland surrounding the tree were utter nonsense: he had had to hack through the tangle of surrounding creepers and undergrowth just to get near the thing. He made a sober botanical assessment – the upas had both male and female flowers, was one of the tallest trees in Java, and was covered in ‘a whitish bark, slightly bursting in longitudinal furrows’. Then he collected some of the poisonous sap and called down carnage on the animal kingdom…

Squatting on the packed earth behind a bamboo hut on the edge of the forest, the botanist was shown how to cook up the upas by and old Javanese man ‘celebrated for his superior skill in preparing the poison’. This rustic toxicologist added all manner of spices to the milky sap, grated in garlic and onion, and then dropped a single chilli seed into the bowl: ‘The seed immediately began to reel round rapidly, now forming a regular circle, then darting towards the margin of the cup, with a perceptible commotion on the surface of the liquor, which continued about one minute’. Another two seeds were added, and when there was no more fizzing and foaming, the mix was declared ready. Horsfield went looking for the nearest dog.

Fur and Feathers

The enthralled listeners of the Batavian Society were treated to detailed descriptions of the effect of upas on 26 different birds and beasts. First up was a ‘dog of middling size’. The unfortunate animal was stabbed in the leg with a poisoned blade, and the fireworks soon began:

In three minutes he seemed uneasy, he trembled and had occasional twitchings, his hair stood erect, he discharged the contents of his bowels. An attempt was made to oblige him to walk but he could with difficulty support himself.

In eight minutes he began to tremble violently, the twitching continued, and his breathing was hasty.

In twelve minutes he extended his tongue and licked his jaws; he soon made an attempt to vomit.

In thirteen minutes he had violent contractions of the abdominal and pectoral muscles, followed by vomiting of a yellowish fluid.

In fifteen minutes the vomiting recurred.

In sixteen minutes, almost unable to support himself, with violent contraction of the abdominal muscles.

In seventeen minutes he threw himself on the ground, his respiration was laborious, and he vomited a frothy matter.

In nineteen minutes violent retching, with interrupted discharge of a frothy substance from his stomach.

In twenty-one minutes he had spasms of the pectoral and abdominal muscles, his breathing was very laborious, and the frothy vomiting continued.

In twenty-four minutes in apparent agony, turning and twisting himself, rising up and lying down, throwing up froth.

In twenty-five minutes he fell down suddenly, screamed, extended his extremities convulsed, discharged his excrement, the froth falling from his mouth.

On the twenty-sixth minute he died.

When Horsfield conducted an autopsy on the poor animal he found evidence of massive haemorrhaging throughout its organs. This ought to have been enough to convince anyone that, yes: upas was very poisonous indeed. But Horsfield was apparently enjoying himself. He decided to try the toxin on a smaller dog. It produced a similarly pleasing performance before the inevitable demise on the thirteenth minute. Next he sacrificed a flying lemur to the gods of science. It was restless; it drooped, and then, of course, it dropped. This was particularly remarkable, Horsfield noted, given that ‘this animal is uncommonly tenacious of life. In attempting to kill it for the purpose of preparing and stuffing, it has more than once resisted a violent strangulation full fifteen minutes.’

Next he tried the poison on an otter, on another dog, and on a pair of small herons. All ended up dribbling and quivering while Horsfield looked on with a notepad and a stopwatch.

The entire experiment had now clearly passed the point of usefulness and was approaching sadistic absurdity, but Horsfield’s own reaction to the upas seems to have been that of an adolescent discovering a wicked new game – ‘Try it on this! Try it on this!’

He tried it on a mouse.

The rodent ‘immediately showed symptoms of uneasiness, running round rapidly and soon began to breathe hastily’. A small monkey, a chicken, more dogs, a cat – none of them lasted more than 20 minutes.

Perhaps the mad scientist was beginning to tire of these common tortures; he needed to think bigger. And so the next victim was an ‘animal of the ox tribe in common domestic use on Java, called Korbow [kerbau] by the Javanese, and Buffalo by the Europeans’.

There was a good deal of enraged bellowing and a ‘copious discharge from his intestines’, but the beast took a full 130 minutes to die. This was too much even for Horsfield; he went back to small dogs and middle-sized chickens.

The audience at the Batavian Society thoroughly enjoyed all this, but even they must have been a little taken aback when Horsfield revealed that for the purpose of his paper he had merely ‘selected from a large number of experiments, those only which are particularly demonstrative of the effects’. A little light upas poisoning had, in fact, become his party piece, and any Europeans visiting him in Surakarta were likely to be treated to the spectacle of at least one dog and one chicken suffering its excruciating effects. It had been a veritable holocaust of fur and feathers, and all to reach the conclusions that ‘The Oopas appears to affect different quadrupeds with nearly equal force, proportionate in some degree to their size and disposition’, that chickens were a little more resistant (the forty-fourth foul fluttered for a full 24 hours; some actually recovered), and that a piece of sharpened bamboo was the best tool for stabbing a buffalo.

Still, at least J.N. Foersch’s tall story had been roundly discredited.

© Tim Hannigan 2012

Posted in Uncategorized